| ISLAND Newsletter - August 2020 |

View in browser | Print |

| | |

Welcome to the August edition of the ISLAND newsletter. I’m Anna King, a research fellow and Associate Director of Research at the Wicking Dementia Centre as well as a National Health and Medical Research (NHMRC) Dementia leadership fellow. I have been with the Wicking Centre since its inception in 2008 and as a cellular neuroscientist I am trying to understand the changes that occur in the brain that cause dementia. The nerve cells in our brain are amazing cells; they need to last a lifetime and they have a remarkable capacity to repair themselves. However, as we get older the repair might not be quite complete and many older people have some “pathological” changes in the brain. These changes don’t usually cause any major problems with the way that the brain works, as the brain has lots of reserves and is quite adaptable. However, for some people this pathology accumulates at a much higher rate, spreads though specific regions of the brain and causes the nerve cells to degenerate. Without functioning nerve cells in the areas of the brain affected, the brain is unable to perform all of its usual functions. Why some people develop these changes and other don’t is something we don’t understand, but there is evidence that our genetics plays a role as well as a number of lifestyle factors. The goal of my research is to develop interventions that protect the brain from these adverse changes. A few years ago, I realized that one of the key limitations to understanding why some people are at risk of dementia and other aren’t, is that the brain is very difficult to study in people while they are alive. This prompted us to look for simple and relatively non-invasive tests we could perform to tell us what is going on in the brain. The brain releases lots of molecules and some of these get into the blood stream in very small amounts. We call these molecules “biomarkers”. Using very sensitive equipment our team is able to measure these proteins in the blood and they can provide us with information about what is going on in the brain. We now want to determine how these “biomarkers” change as we get older, how our genes and lifestyle modify these proteins and how they differ between people who are at high and low risk of developing dementia. With the help of participants in our studies, like yourselves, we hope that in the future we will be able to develop blood tests that will allow us to monitor the health of our brains and to personalize our approach to preventing or treating dementia.

| | What do we mean by 'risk'? |

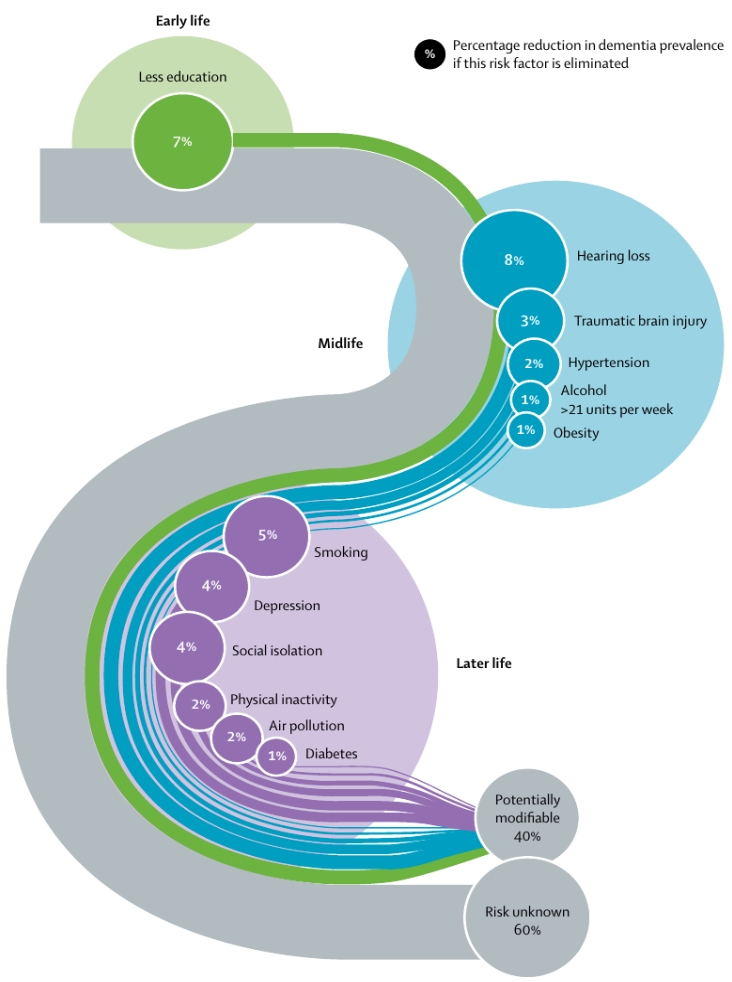

'Risk' is the chance that something will happen, but it doesn't mean something will definitely happen. We know that smoking increases the risk of getting lung disease, but it doesn't mean a smoker is guaranteed to get lung cancer. And you have probably heard of people sadly getting lung cancer but have never smoked. So what about the risk of developing dementia? For dementia, there a mixture of risk factors - some that can be avoided, such as becoming obese, not smoking; or can be modified, such as diet and exercise. Ageing and genes as risk factors for dementia are impossible to control. Therefore, we all have some level of risk for developing dementia, but some of us will have a higher risk than others. For example an 80-year old is much more likely to develop dementia in the next five years than a 30-year old. The Lancet Commission has released an updated set of 12 potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia, together with the percentage reduction in dementia prevalence if a risk factor is eliminated (prevalence is the total proportion of people who have a disease or condition at a single point in time). According to Lancet, the 12 modifiable risk factors account for around 40% of worldwide dementias, "which consequently could theoretically be prevented or delayed". So, for example, 5% of all dementia cases can be attributed to smoking in later life. The new life-course model is below this article. Individually, we can modify our behaviour for each risk factor to reduce our personal risk of developing dementia. For example, we could stop smoking, exercise more, keep our brains active and keep our cholesterol levels in check. Eliminating each risk factor from our life is not a guarantee that we will never develop dementia, because we still have ageing and genetic risks. But by attending to every one of these risk factors, we can reduce our personal risk of developing dementia to as low a risk as possible. According to the Lancet Commission's new model, the incidence of dementia in the population could potentially be reduced by 40% if everyone modified their behaviour and attended to each risk factor (the incidence is the proportion of people who develop a disease or condition within a particular period). But how do we know this? The best kind of evidence for examining dementia risk is to study a large number of people over a long period of time, often called a longitudinal observational study. Researchers also look at the literature on studies about dementia risk and conduct meta-analyses, which pools results from previous published studies on the topic in question to determine how robust the findings are. To achieve this, researchers will question the quality of a study's research design; were the measures taken in the study adequate? Was the study sample big enough to give a statistically robust result? Did the study take into account confounding factors? Researchers will review studies to determine if the findings are reliable, if the limitations of the study mean it's inconclusive, or if there are flaws in the methodology used. The Lancet Commission model has done this for us and provided what is believed to be 12 risk factors for dementia that are backed by robust scientific evidence. There are many studies that appear in the media, which claim that a particular behaviour or item can reduce or increase your risk of developing dementia. Some of these are not supported by the broader scientific community because they are not robust studies. Or, there is not enough evidence to support the findings of a particular study to make a definitive claim. Below are some examples and we will bring you more factual or fictitious dementia risk factors in future newsletter editions.

|  | |

Image: Lancet Commission, 2020: Population attributable fraction of potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia.

Read more

| | State of the evidence - Aluminium |

More hype than hope?

Lots of claims are made about various risk and protective factors for conditions such as Alzheimer’s Disease. Some of these have scientific merit and some of these don’t but, because a lot of them are discussed in the media, it makes it really hard to unpack what is a genuine protective or risk factor and what isn’t. Aluminium is a common metal found in the earth’s crust, in the food we eat and in the water we drink. It has various uses from building cars, trains and other vehicles, right through to more domestic uses, such as pots and pans, cutlery. It’s even used for some cosmetics, such as anti-perspirant deodorant. During the ‘60s and ‘70s, there was a lot of concern that exposure to aluminium might increase a person’s risk of developing dementia. Since then, there have been various studies looking at the different ways in which people are exposed to aluminium and whether this might be associated with an increased risk of developing dementia. In one of the most cited studies in this area, researchers from the UK estimated aluminium consumption via water over a 10 year period. They looked at people who developed Alzheimer’s Disease, brain cancer and other diseases that cause dementia. Their results found no support to suggest that the consumption of aluminium via water would increase your risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease, brain cancer or any other disease. Even exposed to aluminium at high levels, for example a chemical spill, has not been shown to have long term consequences for brain health. To date, there is no evidence that supports a link between every day aluminium exposure and an increased risk of developing diseases like Alzheimer’s or other diseases that cause dementia.

| | State of the evidence - Stress |

Stress is something we all experience throughout our lives. What we do know about stress, is that it can put us at risk of other health complications, like issues with our digestion, increases in our blood pressure, and mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Stress has also been proposed as a potential risk factor for dementia. Some studies have shown that people who report stress consistently throughout their mid-life, may be at greater risk of developing dementia later in their life. However, the mechanism through which stress affects dementia risk hasn’t been adequately tested. Some researchers think that stress may have an indirect relationship to dementia risk. For example, it is well established that stress can increase your blood pressure. It is also established that increased blood pressure may put you at risk of cardiovascular disease. Both high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease are risk factors themselves for developing dementia. So you can see that reducing your stress may help reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease, it may help reduce your blood pressure, which in turn may help reduce your risk of dementia. As another example, some studies have shown that people with stress-prone personalities, or those high in neuroticism, may be at a greater risk of developing dementia. This may be because they spend significantly less time socialising with family and friends. Having significantly less social interaction may contribute negatively to an individual’s overall risk of developing dementia. Stress cannot be completely avoided, but managing our stress can be very beneficial to our overall physical and mental health. Currently, there is no evidence to suggest a direct link between stress and dementia.

| | |

How chronic stress affects your brain

This TED-Ed video explains how chronic stress affects the brain, changing its size, its structure and how it functions.

TED-Ex-How chronic stress affects your brain

| | ISLAND Project Partners | |

|  | |

The University of Tasmania received funding from the Australian Government. Views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of its authors, and may not be the same as those held by the Department of Health.

|

|

Stay Connected:

|

|

islandproject.utas.edu.au

|

| |

|

|